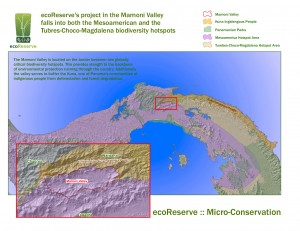

ecoReserve’s first reserve located in the Mamoni Valley is part of the Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena Hotspot and includes a small portion of the Chocó/Darién wet region, one of the two major regions in the hotspot.

ecoReserve’s Mamoni Valley reserve falls in two of the 34 internationally recognized biodiversity hotspots: 1) the Mesoamerica Biodiversity Hotspot and 2) the Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena Hotspot. Although both start in Panama, the Mesoamerica Biodiversity Hotspot runs northward, but the Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena Hotspot runs southward. Because we have already discussed the Mesoamerica Biodiversity Hotspot, this post will focus on the Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena Hotspot. The Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena Hotspot starts in the southeastern portion of Mesoamerica and extends to the northwestern corner of South America with a reach of 1600 kilometers, which is close to 1000 miles. The hotspot is divided into two main regions, the northernmost Chocó/Darién wet and moist forests located in the Darién Province in Panama and the Chocó region in western Colombia to the southernmost Tumbesian dry forests of Ecuador and the northwestern part of Peru.

The Darién Province is one of the most diverse, remote regions in Central America and is protected by dense pristine forests and jungle. At over 3 million acres, it is the largest province in Panama, the most sparsely populated, and the least well known. It is a region of dense tropical rainforest and is among the most complete ecosystems of all tropical America. The Darién is mostly uninhabited mountains, jungle, and swamplands, and it has one of the richest ecosystems of the American tropics. It is also home to many endangered species, such as the jaguar, the giant anteater, the harpy eagle, and the tapir.

Until 20 years ago, there were no roads in the Darién, and travel through the region was very difficult. Before the roads were built, the indigenous people of the area, the Embera, Wounaan, and Kuna, relied mainly on water transportation because they live in settlements scattered along the river valley . Today the Pan-American Highway cuts through the middle of Darien. This gravel highway extends down as far as the town of Yaviza, which is the beginning of the famed Darien Gap. This 100 km gap, which is the only uncompleted piece of the the Pan-American Highway, is impossible for travelers to pass and survive. The highway poses another danger as well. Because the highway connects overland commerce between North and South America, it has opened up the region to cattle ranchers, loggers, and landless peasants. As a result, both the natural forest and the indigenous people of the Darién are being threatened.

The biggest objection to completion of the highway is its effect on the region’s ecological balance and the danger it poses to the survival and habitat of the indigenous people living in the region. It would also extend the already dramatic deforestation of the area.